Amiga PD CharitywareAmiga PD is a charityware site - if you download any disk images you are encouraged to donate to our chosen charity - Mencap - at our justgiving page.

Suggested donations are £1 per disk image download as this was the cost of obtaining a disk back in the 1990s. Thank you. |

|

|

|

INTERVIEW WITH MARK GALLAGHER

Amigapd would like to thank Mark Gallagher for agreeing to answer some questions about his amiga games.

To download disk images for Smash TV the Rip off please visit his website. This interview was completed October 2013. |

How did you first get involved in computer programming?

Mark Gallagher (MG): I got a Spectrum 48k for my 13th birthday and used to type in listings from magazines. It was amazing to me at the time that with a couple of lines of basic you could have stuff showing up on the screen. The assembly language bit of it happened little by little. It started off with me getting frustrated at not having enough lives, so I’d hunt through the code using PEEKs to find out where any memory location was set with a 3 or a 5 (or however many lives you got). Once I’d found that, I’d look for where it decremented that memory location and NOP it out and from there you can sort collision detection to make you immortal. Pretty simple really, but it gave me a hunger for more and I ended up doing a few rubbish demos on the Spectrum.

The coding really took off when I got a C64 and joined a computer club that Barry Leitch had told me about (thanks Baz!) that had people that could program properly. I learnt pretty quickly and was soon coding some half decent demos and a couple of half-baked games in 6502 (most of which can be downloaded off the site).

The coding really took off when I got a C64 and joined a computer club that Barry Leitch had told me about (thanks Baz!) that had people that could program properly. I learnt pretty quickly and was soon coding some half decent demos and a couple of half-baked games in 6502 (most of which can be downloaded off the site).

How easy did you find the transition from programming 8 bit computers (C64s) to 16 bit computers (Atari Sts) and what challenges did the new technology bring?

MG: I think I was 16 or 17 when one of my friends, who was already an established programmer lent me Devpac and a couple of Atari STs with a cable to upload the code. I already had a couple of books on 68000 and had been coding 6502 for about 3 or 4 years so I didn’t really have too much trouble figuring out what all the commands were for. It only took a couple of weeks to get competent and comfortable with 68000.

How different were the Amiga and Atari ST to program and how did they vary in terms of developer tools?

MG: I used to use Devpac on the Atari ST, but once I started coding for a software company I was given a SNASM development system. I think it was a company called Cross Products that created SNASM. The kit consisted of a modified SCSI card which fit in an ISA slot in a PC (I used a 286) which was connected to an interface that was plugged in to the expansion port of the Amiga or ST. I used Borland Brief for development. Brief was a customisable text editor and back in the early 90s it was the development tool of choice for games programmers as well as more business orientated coding. You’d basically write your code and then press whatever key combination macro you’d chosen to check the code and punt it down the cable to the Amiga. The good thing about SNASM was that you could stop your code at any point and then single step through it to check for bugs while viewing all the registers and variables. That’s all standard stuff now, but it was a real step up for me at the time to have that amount of control.

What was it about Smash TV that made you want to make a conversion of the game?

MG: I was working as a bicycle messenger at the time and was looking for a coding project to do in the evenings, I went into the arcade and saw Smash TV and that was me hooked. It was the simplicity of it coupled with the playability and frenetic action. I actually wrote pretty much all of it on the ST, but the frame rate was atrocious once things got going. I think it was running around 6 or 7 frames a second! I took the code into the office at Christmas time and ported it onto the Amiga in a weekend. The change in frame rate was noticeable straight away – amazing what a bit of blitter can achieve! I was getting around 25 frames a second with little or no drop once the action started.

How did you research the game mechanics of Smash TV, did you just play the arcade machine or did you make notes and drawings too?

MG: I went into the arcade and watched someone playing it to get an idea of how the patterns worked and rough numbers. I don’t remember, but I must’ve taken a notepad to jot down what was going on in each of the levels or screens. It’s obviously not a true copy of the game graphically or pattern wise. I was more interested in capturing the insanity of it - I spent ages tweaking the movement of the player and the baddies so that it felt right when playing

Most of the reviews of Smash TV the Rip Off were of the opinion that the game was better than the commerical release, were you surprised by the positive reaction?

MG: I was really surprised at the reaction, all I did was code a game that I liked to play – that’s what it’s all about at the end of the day. I was more surprised that Ocean, of all companies, had done such a poor conversion. I grew up playing Ocean games on the Spectrum and 64 and their games were always brilliant. It was a bit disappointing that they came out with such a lacklustre version on the Amiga. I think it was Probe that did the actual development of it.

I’d always intended to put more levels on it. I thought I’d put it out as a demo with a view to adding more levels later, but various circumstances stopped that from happening, so it’s a pretty quick finish. The biggest surprise I think was that people sent me money even after they’d played it – they liked it that much – gave me a real sense of pride. If anyone’s reading that sent me money – thanks!

I’d always intended to put more levels on it. I thought I’d put it out as a demo with a view to adding more levels later, but various circumstances stopped that from happening, so it’s a pretty quick finish. The biggest surprise I think was that people sent me money even after they’d played it – they liked it that much – gave me a real sense of pride. If anyone’s reading that sent me money – thanks!

Did you consider adding music to the game?

MG: It did cross my mind, but the only musician I was really in contact with at that time was Barry Leitch and he was up to his eyes in work, so didn’t want to bother him! I don’t think the lack of music takes anything away from the game – the sound effects make up for it.

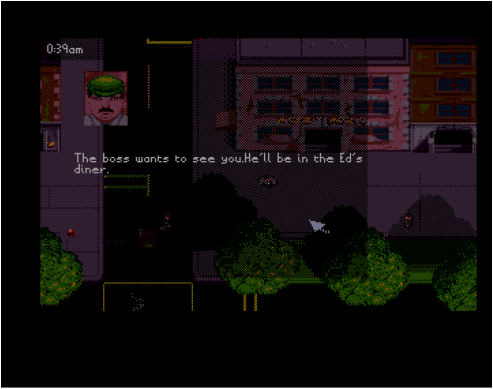

How complete is Crime Inc?

MG: We got paid for 6 out of the 10 milestones before it got shelved. The Amiga just wasn’t powerful enough to handle all the stuff we were wanting to do. Looking back, I could have probably done some stuff to reduce the CPU time being used. As far as I can remember there’s a couple of missions you can play. I think we can take credit though for having created the first ever sandbox game (happy to be corrected, but I’m pretty sure it is).

How did you imagine the final version of Crime Inc would have looked if it had been released?

MG: Much the same as the version that can be downloaded, only with a full mission complement and a completed conversation system. The mechanics are complete, but there’s not much content. We were aiming for a gritty 1930s Chicago look. I think we were trying to do too much for the platform it was on though. We had weather effects, day and night, leaky fire hydrants, 30 cars driving about, following the rules of the road, slowing down for pedestrians, 150 people walking around all doing their own thing. It was pretty big for back in the early 90s. Plus because it was sandbox, you could just do whatever you wanted instead of completing the missions….

What part of the game making process did you enjoy most, designing the concept of the game or the actual programming?

MG: The planning bit can be quite fun as ideas get fired about, but nothing can beat the process of creating something from nothing. You start with a blank canvas and next thing you’ve got things moving about on screen and you’ve got interaction going on and the game’s taking shape.

Do you regret leaving the computer gaming industry?

MG: Sometimes. It’s a different world to the way it was though. Instead of a team of 1-3 creating a game, you’ve got literally hundreds of people involved. It’s big business now and I’m not sure if I’d enjoy it in the same way as I used to. There’s so much dross about as well, a lot of companies seem to be putting a quick buck in front of playability or creating and engaging title. If I was going to do games again, I’d have to do it on my own terms. I’ve got friends who still work in the industry who have little or no control over the game creation process – they’re basically told “right, you’re doing this”. I wrote games because I have a passion for gaming, you don’t want to get stuck on a product you have no interest or passion for.

I still code on a regular basis, but it’s not my day job. I write Windows and web based apps, some with commercial potential. I’ve been thinking about doing iPhone games, but it’s finding the time and the motivation…

I still code on a regular basis, but it’s not my day job. I write Windows and web based apps, some with commercial potential. I’ve been thinking about doing iPhone games, but it’s finding the time and the motivation…

What advice would you give a young programmer starting out in the computer game industry today?

MG: Try and work on games that you’d want to play yourself, not the easiest thing to do these days! I think it’s important to have a passion for gaming because that can help drive the creative process. Work hard and try not to compromise too much if you believe in something. Don’t be afraid to try new things…

I know this is pretty obvious, but I’m going to say it anyway - playability is the single most important thing about a game – it can have the most awesome graphics, fantastically designed maps and a great idea, but if the user interface is clunky or it’s hard to play, it brings the whole thing down. Simple is good, Angry Birds is a classic example – simple game – tens of millions sold.

I know this is pretty obvious, but I’m going to say it anyway - playability is the single most important thing about a game – it can have the most awesome graphics, fantastically designed maps and a great idea, but if the user interface is clunky or it’s hard to play, it brings the whole thing down. Simple is good, Angry Birds is a classic example – simple game – tens of millions sold.

Thank you

AmigaPd would like to thank Mark Gallagher for taking the time to answer these questions.

AmigaPd Charityware

We hope you enjoyed reading the interview - remember AmigaPd is charityware - please visit our just giving page to support our chosen charity Mencap.